What would a Bernie Sanders administration mean for the economy and markets?

With the Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada largely behind us, and South Carolina tomorrow, the likelihood that Bernie Sanders will be the Democratic nominee for president has grown. 538 now places this probability at 40%. We believe it is time to meaningfully engage with this possibility and consider what it would mean for the US economy and the markets.

Our analysis will go beyond the conventional view that even if elected president, Senator Sanders will be unable to enact his ambitious agenda. For example, Sanders’ wealth tax proposal would apply to fortunes over $32 million (the top 0.1% of all American households). JP Morgan recently estimated the likelihood of any wealth tax being implemented at 5%. We would say the probability that some of Sanders’ major proposals are enacted is closer to 25%.

In our view, Sanders’ agenda is a robust response to rising income inequality and market failures in the 21st century. His biggest proposals, Medicare for All and College for All, enjoy majority support among voters. There is evidence to suggest US voters (particularly younger ones) are not as ideologically fixed as many assume. Lastly, since his initially quixotic 2016 campaign, Senator Sanders has succeeded in expanding the overton window, i.e. what is considered possible in US politics. We take his agenda seriously.

A full consideration of Sanders’ program will require more than a single blog post. We choose to begin with a look at Senator Sanders’ signature policy proposal, his Medicare For All plan. Other major policy proposals and stances will be considered in later installments. We should however, make some general thematic remarks on Senator Sanders policy platform.

- Senator Sanders’ proposals are often presented as “radical”. In truth, they match the social democratic policies in place across much of Europe and the rest of the industrialized world. Proposals such as College for All align well with past US policy. College tuition at most public colleges in the 60s/70s was either very low or free.

- Some of Sanders’ more ambitious policies attempt to tackle systemic risks related to market failures. His proposals to address climate change, extreme inequality and breaking up the largest banks are pretty conventional prescriptions to address the market’s inability to price externalities, protect the rule of law, and prevent speculative credit crises respectively. There is a case to be made that such measures would make our economic system more resilient and lay a lasting architecture for prosperity.

- Many of Sanders’ policies have been enacted in other parts of the world so we have a benchmark to compare against. The United Kingdom, France, Italy and Canada have single-payer healthcare systems, few would claim this has impacted their long-term growth negatively. If anything, there is some evidence that the unpredictability of health care costs in the US has driven industrial production towards Canada, where a single payer system equalizes costs among employers.

We should also note that improving the health, well-being and longevity of the human population is a valuable and laudable goal. Even when using the narrow criteria of economic/GDP growth, healthcare and public health are critical. Our economy depends on human ingenuity to add value to material resources. Health and well-being are necessary to make this possible. The public health crisis that is the COVID-19 virus outbreak brings this into sharp relief. The rapid spread of this virus has already impacted economies and markets on multiple continents. Healthcare systems that are free at the point of service, with a strong primary care network lead to early diagnosis and response to such outbreaks. Imagine a healthcare system where people who are sick do not visit the doctor because they cannot shoulder the costs, or worse yet, continue to work because they do not have paid sick leave. Both have deleterious effects on short-term economic activity and long-term potential, by impacting human capital.

Earlier this year, the White House proposed cutting funding for the CDC, just as this outbreak gathered steam. This was on top of the administration’s earlier decision to fire the entire pandemic response team. These measures may result in minor short-term savings but have lead to a stark increase in potentially catastrophic risks.

Medicare For All

We assume most readers are familiar with the contours of Senator Sanders’ Medicare For All proposal. The highlights:

- creates a “public option” in the first year

- expands Medicare services to cover dental, vision, long-term care and all necessary medical procedures

- eliminates co-pays and deductibles, making healthcare free at point of service

- covers the cost of all prescribed medications

- expands eligibility to cover all US residents over four years, creating a single-payer healthcare system

- private insurance is prohibited from covering services covered by Medicare For All

- eliminates all past-due medical debt

- Medical service providers (hospitals, doctors, laboratories) continue to operate independently and bill Medicare for services.

If enacted, this proposal would make health insurance companies largely obsolete. Some rump services (elective surgery, health insurance for foreign travelers, etc.) would survive. Most health insurers would shrink to other insurance lines (P&C, life, liability etc.). Service providers that refuse to accept Medicare and its reimbursement rates would be left with a small pool of US patients who can afford to pay for medical services entirely out of pocket.

This is clearly negative for the health insurance industry. The proposal includes funding to retrain workers and help them find work, but there is no such provision for businesses. The US spends an outsized amount on healthcare, Senator Sanders claims his proposals would reduce this fraction while expanding coverage. This is only possible if the system reduces costs significantly.

If a single-payer system is implemented in the US, it would almost certainly reduce costs. Some of this would come from lower overhead. Health insurance companies typically expend 20% of their revenues on costs other than reimbursement for medical services. In contrast, the current Medicare system operates at a much lower 3% overhead. Most observers also believe additional savings would be realized by delivering timely primary and preventative care to all, rather than expensive emergency care when maladies have become worse.

A detailed study published in The Lancet arrives at similar conclusions:

Taking into account both the costs of coverage expansion and the savings that would be achieved through the Medicare for All Act, we calculate that a single-payer, universal health-care system is likely to lead to a 13% savings in national health-care expenditure, equivalent to more than US$450 billion annually (based on the value of the US$ in 2017). The entire system could be funded with less financial outlay than is incurred by employers and households paying for health-care premiums combined with existing government allocations. This shift to single-payer health care would provide the greatest relief to lower-income households. Furthermore, we estimate that ensuring health-care access for all Americans would save more than 68,000 lives and 1.73 million life-years every year compared with the status quo.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)33019-3/fulltext

Under Medicare for All, medical service providers would also face restructuring. Medicare’s reimbursement rates are generally lower than those offered by private plans. This may be partially offset by eliminating the complexity involved in billing thousands of health insurers and millions of individual patients. Since Medicare is a reliable payer, the effort and expense involved in managing unpaid bills would disappear for most health practices. These assumptions are validated by a survey of academic literature in the academic journal PLOS Medicine:

We found that 19 (86%) of the analyses predicted net savings (median net result was a savings of 3.46% of total costs) in the first year of program operation and 20 (91%) predicted savings over several years; anticipated growth rates would result in long-term net savings for all plans. The largest source of savings was simplified payment administration (median 8.8%), and the best predictors of net savings were the magnitude of utilization increase, and savings on administration and drug costs (R2 of 0.035, 0.43, and 0.62, respectively).

https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013

The benefits of Medicare for All would accrue to a broad cross-section of individuals and employers:

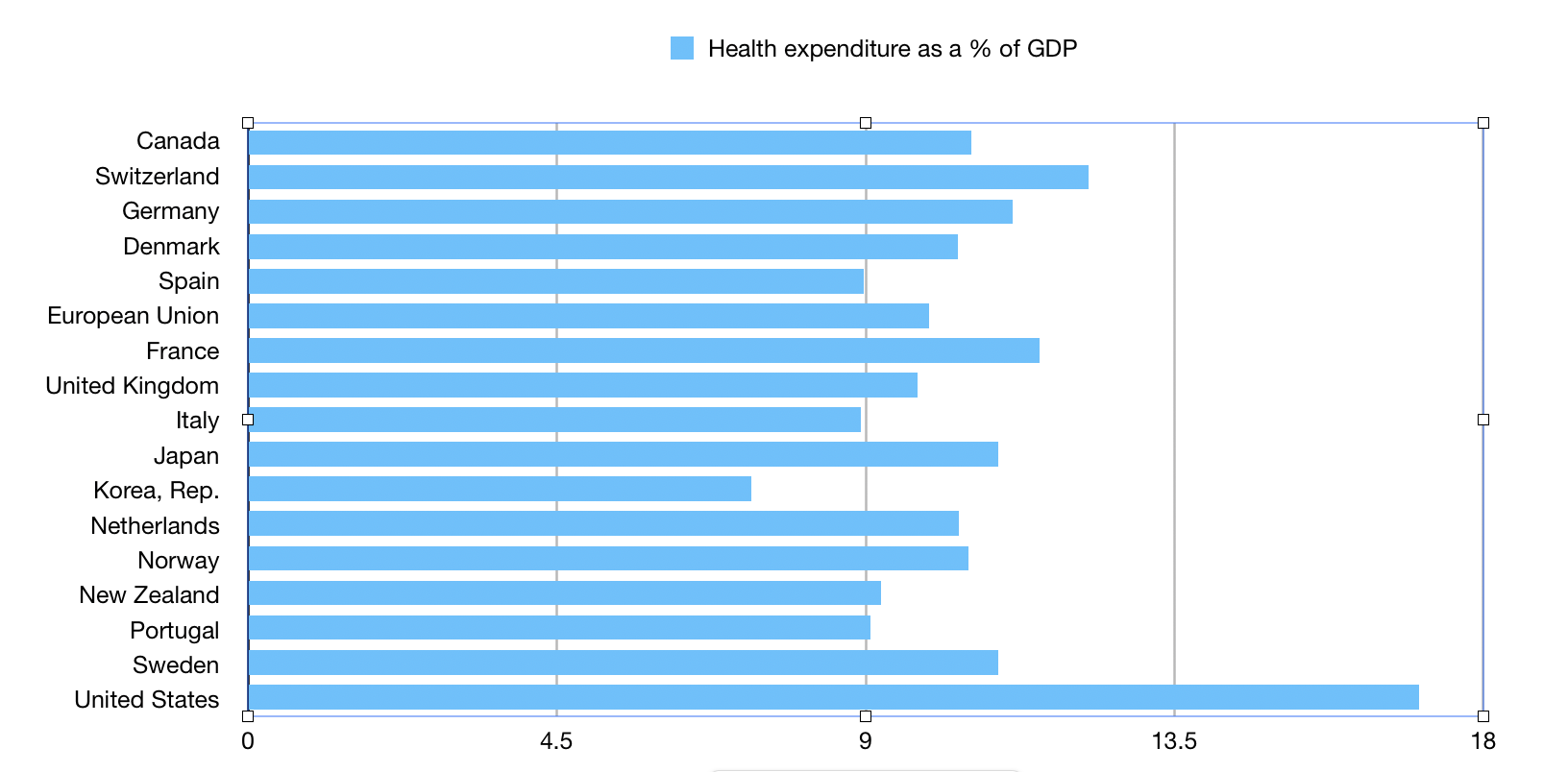

- Health-care costs should begin to trend downward over time, from roughly 16% of GDP currently, to the 8-10% average across OECD countries.

- Individuals would be guaranteed health-care free at the point of service. Our expectation is that this will quickly lead to better health outcomes across the US, eventually matching other developed countries.

- US life expectancy should rise over time from the current 79 years to approach Canada’s 82 years.

- US infant mortality rates should also fall from 6.5 per 1,000 live births to Canada’s 5.0.

- By removing all cost-related barriers to health care, Medicare For All should result in increased use of preventative healthcare. This in turn should lead to a healthier work-force, increasing productivity.

- Employers would no longer have to expend significant resources to evaluate, choose and maintain health insurance plans for employees.

- Individuals would no longer have to expend time and effort on choosing plans and battling for reimbursement when they have medical expenses. By our estimate, this should result in a time savings of 2 days for every person in the US.

- Almost 79 million US residents have medical debt. Academic research suggests such overhangs reduce economic activity and consumer spending. Medical debt also leads to hundreds of thousands of bankruptcies each year. Wiping out such debt should have a positive effect on growth.

- Labor mobility should be improved by instituting universal healthcare that is free at point of service. The academic literature is quite clear that employer-linked health insurance reduces labor mobility and locks employees to jobs that may not be a desirable. COBRA does alleviate some of these concerns, but not entirely.

With such varied effects, it is difficult to estimate the overall short and medium term impact on US economic activity overall. From the experience of other industrialized economies, it seems clear that investments in public health improve long-term economic prospects. Taken together, these effects could add up to several points in additional GDP growth over 10 years.

We generally assume that the market reaction to a Sanders’ Medicare For All enactment will be negative to flat. Health markets in most jurisdictions do have some sort of price control and there is a case to be made for them in a market with the sort of information disparities and local monopolies that health care has. Yet many market participants instinctively recoil from price controls and our assumption is that the general market reaction to a single payer plan will be negative. Any longer-term impacts will take a while to materialize. Sanders’ proposals to raise capital gains rates, implement wealth taxes and a capital markets transaction tax are all more likely to affect market sentiment.

We will evaluate Senator Sanders’ College for All proposal in a later post, for now, we will note that home-ownership and head-of-household rates for adults in their 20s, 30s and 40s have been declining since 2007 and never recovered. That is a very strong indicator of lasting debt overhangs.

Senator Sanders’ argument for a student debt-forgiveness program relies on two facts:

- it would return the US to a past policy that was successfully implemented for decades. Public university tuition at most land-grant colleges, large systems like CUNY and U.Cal/Cal-State was tuition-free or very low cost till the 60s.

- forgiving student debt would allow deeply indebted graduates an opportunity to embark on household formation without the burden of a debt overhang.

Each of these claims should be evaluated on its merits. We are skeptical of arguments relying on conventionally accepted political principles that dismiss this reasoning out of hand (eg. “it would never work”, “it is too costly”, “it’s insane”). There are several industrialized economies where higher education is free or very low-cost, these can serve as a model for analysis.